- The Art of Adapting: Lichens and Nature's Infinite Combinations

- Restoration Between Science and Patience: How Lichens Are Removed

- How to Manage Lichens (Without Damaging the Stone)

- Cyanolichens: The Ancient Alliance Between Fungi and Cyanobacteria

The Art of Adapting: Lichens and Nature's Infinite Combinations

The different lichen species have varying needs, which is why they are able to effectively colonise the numerous ecological (micro-)niches found in every environment.

-

Learn more...

The distribution of lichen species is influenced by various factors, including light intensity, inclination and exposure of the substrate, temperature, availability of liquid water, presence of dissolved mineral substances, and the supply of (micro-)nutrients such as nitrates from bird droppings. Even stone artworks exposed to the outdoors form ecosystems with numerous micro-niches, which can be colonised by complex and diverse communities.

Restoration Between Science and Patience: How Lichens Are Removed

Lichens on stone cultural heritage can cause biodeterioration in most cases: for this reason, their removal is typically required during the restoration process.

-

Learn more...

Although the growth of lichens in archaeological sites is inevitable, there are several ways to devitalize and remove them, when necessary. Over the past few decades, many studies have focused on this issue, providing valuable insights, such as the importance of devitalizing the thalli before their mechanical removal from surfaces. Several factors, such as the sensitivity of different species to commercially available biocides and the various application protocols, play a crucial role in the success of interventions and, above all, in the longevity of their effectiveness.

How to Manage Lichens (Without Damaging the Stone)

Before removing the lichen thalli, it is important to devitalize them. In this way, we prevent lichens from resuming colonisation immediately after cleaning, especially from portions that remain within the stone.

-

Learn more...

Devitalization can be achieved through physical methods, such as exposing hydrated thalli to temperatures rapidly raised above 50°C, for example using microwaves. The use of ablative lasers is also considered a physical treatment. There are also chemical methods involving biocides, substances toxic to organisms. The effectiveness of biocides, whether synthetic or plant-derived, depends on various factors: the sensitivity of each lichen species, the concentrations and solvents used, the timing and methods of application (such as brushes or cellulose pulp poultices), and the humidity and temperature conditions during treatment. For this reason, it is essential to perform preliminary tests to verify the effectiveness of treatments.

Cyanolichens: The Ancient Alliance Between Fungi and Cyanobacteria

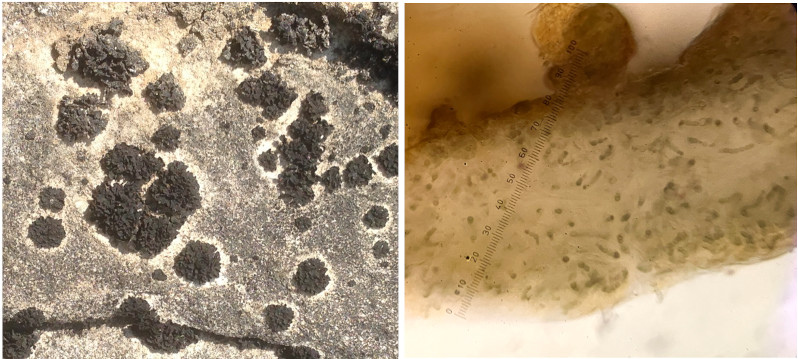

Cyanolichens are black and compact. They are brittle and hard when dry, but become gelatinous and expand in volume when wet.

-

Learn more...

Cyanolichens are lichens in which the mycobiont forms a symbiosis with cyanobacteria, photosynthetic bacteria that, in Earth's history, were the first to perform photosynthesis, releasing oxygen into the atmosphere. Today, we find them in many environments, even outside the lichen symbiosis. The thalli of cyanolichens can be crustose, foliose or (micro)fruticose, and in many cases, they have a homeomeric structure (explore further at STATION 1). Unlike lichens in symbiosis with green algae, which can use water vapour for rehydration, cyanolichens rely on liquid water, at least periodically, for their metabolism.