- What Type of Rocks Do We Live On?

- How Do We Grow on and Inside the Rocks?

- We Damage the Rocks...

- …Or Do We Protect Them?

What Type of Rocks Do We Live On?

The growth of lichens is influenced by the type of rocky substrate, whether natural or artificial. Many species prefer specific types of rock: siliceous (sandstone, tuff, granite) or calcareous (marble, travertine, calcarenite).

-

Learn more...

Some rocks, such as calcareous sandstones, can support both silicicolous and calcicolous lichens. The eutrophication of rock surfaces – that is, the input of nitrogenous substances from fertilisers and/or bird guano – promotes the growth of certain species, called nitrophiles, on all types of substrates. The pH, water availability, and degree of eutrophication of the stone are important ecological factors for the establishment of lichen communities.

How Do We Grow on and Inside the Rocks?

Lichens growing on stone can be either epilithic or endolithic.

-

Learn more...

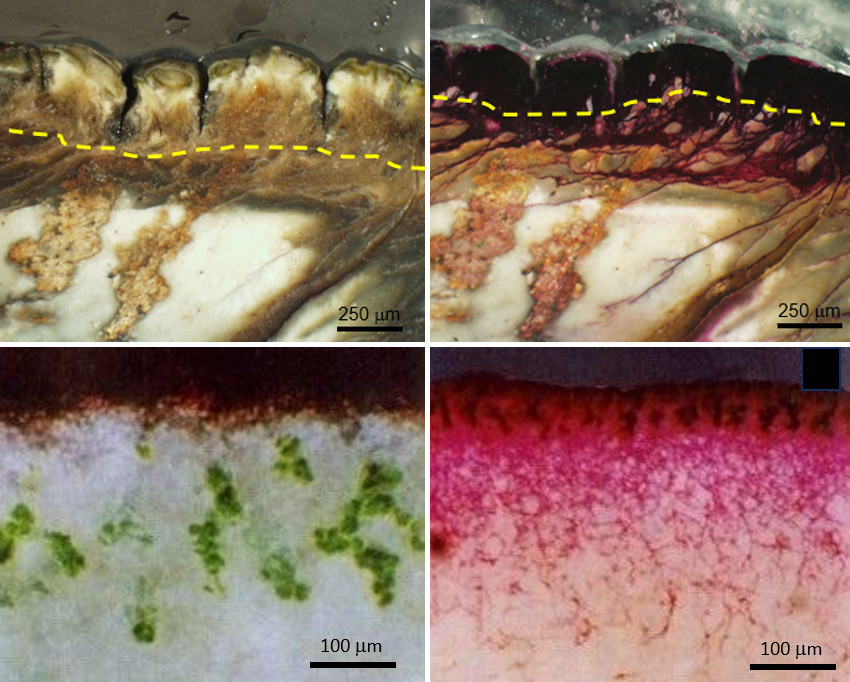

Epilithic lichens are easy to spot: their thalli grow on the surface of the stone and, in many cases, are characterised by bright colours such as yellow, orange, and green. However, the fungal structures (hyphae) do not just stay on the surface – they also grow into the pores of the substrate, anchoring the thallus securely. Endolithic crustose lichens, often overlooked but of great scientific interest, are much less conspicuous, as they are completely embedded in the rock, with both the hyphae of the mycobiont and the cells of the photobiont penetrating the substrate. Like other endolithic organisms (such as free-living cyanobacteria, algae, and fungi), they colonise the outer layers of limestone rocks, slowly dissolving calcite crystals and carving out tiny tunnels that can reach a depth of a few millimetres.

We Damage the Rocks...

Lichens are among the first pioneer organisms to colonise rocks and accelerate their deterioration through both physical and chemical processes, such as the diffusion of hyphae inside the stone (which can penetrate more than 15 mm), the expansion and contraction of thallus during wet and dry periods, and the secretion of organic acids that promote the dissolution of the mineral substrate.

-

Learn more...

Lichen acids are capable of “chelating”, meaning they bind metals contained in the rock like the claws of a crab. In this way, the minerals are altered, and the process of soil formation (pedogenesis) begins. The fruiting bodies of endolithic crustose lichens are specifically located within small cavities in the stone, which are produced by the lichen itself. When they die and detach, they leave behind a characteristic phenomenon on the surface called “biopitting”. These small cavities provide an ideal substrate for subsequent chemical and/or biological aggression.

…Or Do We Protect Them?

In certain combinations of lichen species, rock type, and climatic conditions, lichens do not cause significant damage to the substrate, and can even have a protective effect. In some cases, they help to slow down the degradation of the stone by shielding it from weathering and pollution.

-

Learn more...

Lichens can protect the surfaces they colonise by forming a kind of barrier against wind abrasion, the infiltration of water, pollutants, salt aerosols, and more. They can also help consolidate and strengthen the stone surface by producing biomineral deposits, and they help reduce temperature and humidity fluctuations inside the material. Whether lichens are more helpful or harmful depends a lot on the physical and chemical characteristics of the rock they grow on. In fact, biodeterioration and bioprotection often happen together – and it is their delicate balance that determines the impact of lichens on stone materials.