Living Together

Lichens are the result of a mutualistic symbiosis – a stable relationship between different organisms that live together and benefit from one another. There are over 15,000 known lichen species worldwide. Many of the surrounding stone surfaces, as well as some trees, are richly colonised by lichens.

-

Learn more...

When we talk about lichens, they are often described as a symbiosis between a fungus, called the mycobiont, and an alga, called the photobiont. Although this definition is correct, it does not fully reflect the complexity and diversity of lichen symbioses. In some species the photobiont is represented by a population of microscopic green algae, while others contain a population of cyanobacteria – bacteria able to photosynthesise (explore further at STATION 5). In some cases, three partners are involved: a mycobiont in association with both green algae and cyanobacteria. We can also observe more complex situations, where colonies of non-photosynthetic bacteria and additional fungi are present. Lichens resemble small ecosystems, in which each partner plays a functional role. To put simply, the mycobiont forms the body of the lichen, called the thallus, and protects the photobiont (algae or cyanobacteria), which provides nutrients to all partners by producing sugars through photosynthesis.

What Are We Like Inside?

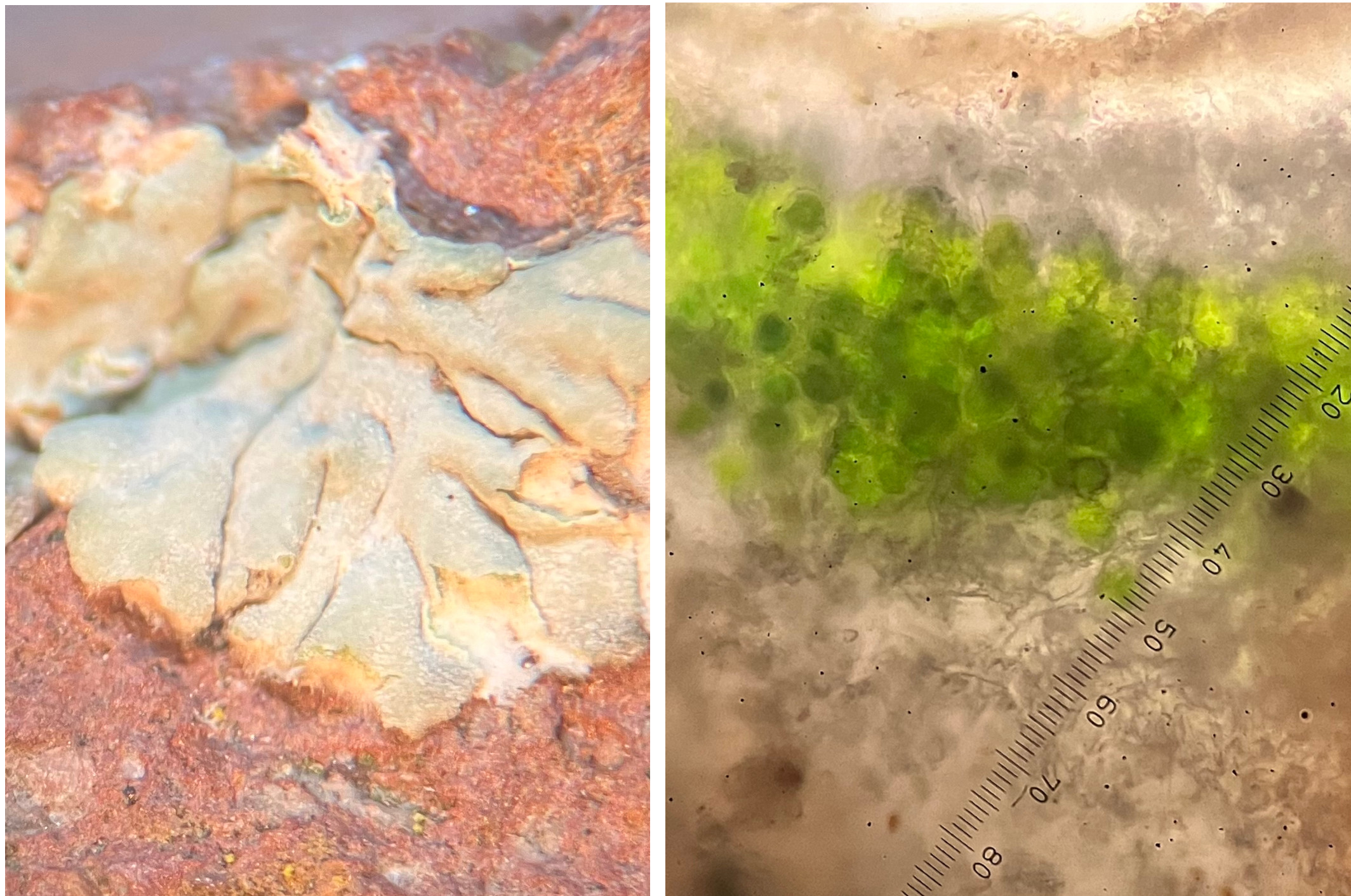

Inside the lichen thallus, the mycobiont and photobiont are arranged differently depending on whether the anatomical structure is stratified, as shown in the photo, or whether it presents a uniform network of fungal filaments (called hyphae) and algal or cyanobacterial cells.

-

Learn more...

Depending on the species, the interaction between the different partners can give rise to different anatomical structures of the thallus. In many species, the thallus is heteromerous, meaning it is organised into structurally and functionally distinct layers, with the algae concentrated in a clearly defined layer known as the gonidial layer. In other cases, the thallus is homeomerous, meaning it shows no stratification, and the mycobiont filaments (hyphae) and the photobiont form a uniform, undifferentiated network.

And On the Outside?

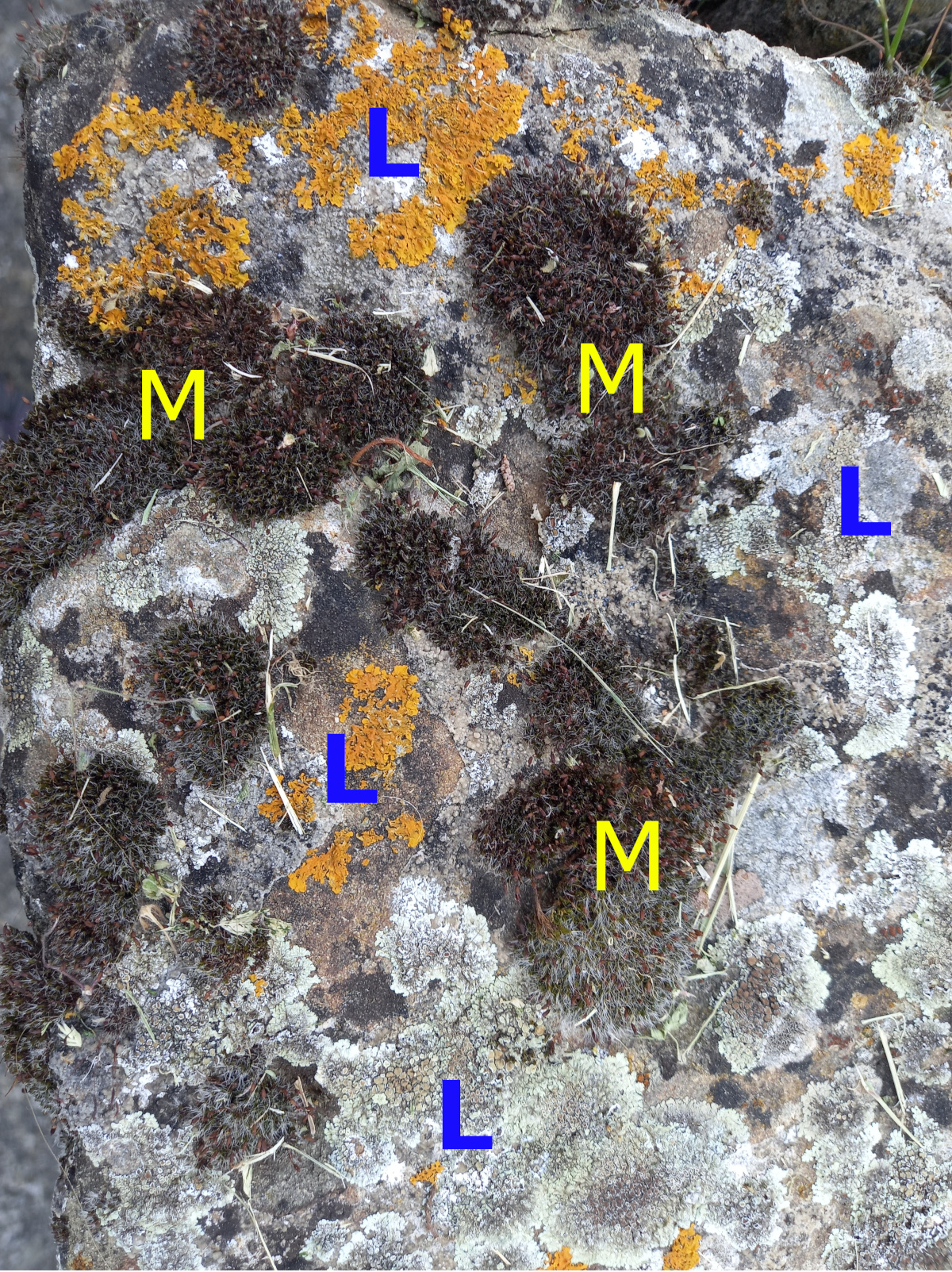

Despite the simplicity of the organisms involved in lichen symbiosis, we can observe many different forms. These can be grouped into three main types: crustose, foliose, and fruticose.

-

Learn more...

Lichens can exhibit different growth forms. In crustose lichens, the thallus appears as a crust, firmly attached to the substrate, from which it cannot be removed without damaging the integrity of the thallus. In foliose lichens, the thallus, similar to a leaf, has a laminar structure with an upper and lower surface. The latter can attach to the substrate with filamentous structures called rhizines. In fruticose lichens, the thallus has a three-dimensional, branched growth and can take on various forms, either upright or pendent.

Where To Find Us

Thanks to their physiology, lichens are capable of living and adapting to any terrestrial environment, although they do not grow in the sea. Lichens can thrive in forests and tundras, as well as in hot deserts and riverbeds, on the highest mountain peaks, in polar regions, and even in our cities. Recent studies have shown that lichens, at least for short periods, can even tolerate simulated extraterrestrial conditions.

-

Learn more...

The surprising ability of lichens to colonise even extreme habitats is due to two special characteristics: the first is that the hydration state of their thallus is always in balance with the humidity of the surrounding environment (poikilohydry); the second is their ability to switch off their metabolism in cases of severe dehydration (cryptobiosis). Thanks to these adaptations, lichens can maintain photosynthetic activity and survive periods of environmental stress.

Lichens are incredibly adaptable organisms and can grow on a wide range of surfaces, both natural and artificial. Some colonise the soil (epigeic or terricolous species), while others grow on trees (epiphytes): here, mostly on the bark and branches (corticolous), but in tropical areas, also on leaves (epiphyllous or foliicolous). As you can see around you, many lichen species settle on rocky surfaces (saxicolous), whether natural or man-made, developing their thallus either on the surface (epilithic) or inside the stone (endolithic). Even artificial materials are not safe from lichen colonisation: you can find lichens on road signs, benches, railings, as well as on glass, leather and shading cloths… and the list goes on!